From Concept to Product

Left: Patent 3,142,567, July 28, 1964. Polaroid Corporation Legal and Patent Records, b. II.165, f. 12.

Right: Patent 2,435,720, Feb. 10, 1948. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, b. VII.10, f. 24.

In 1948, referring to its commercial release of instant photography that year, Land acknowledged the considerable expenses involved in the commercial launch of the new medium and his hopes for company earnings to pass the break-even point.(1) Eudoxia Muller, one of the early researchers with whom Morse worked on instant photography, remembered that Land “had to fight for the SX-70 research; it was not financially certain, nor was it a war-time project. Land persisted and the work . . . continued, expanded, & was the big financial break-through the company needed in the post-war years.”(2)

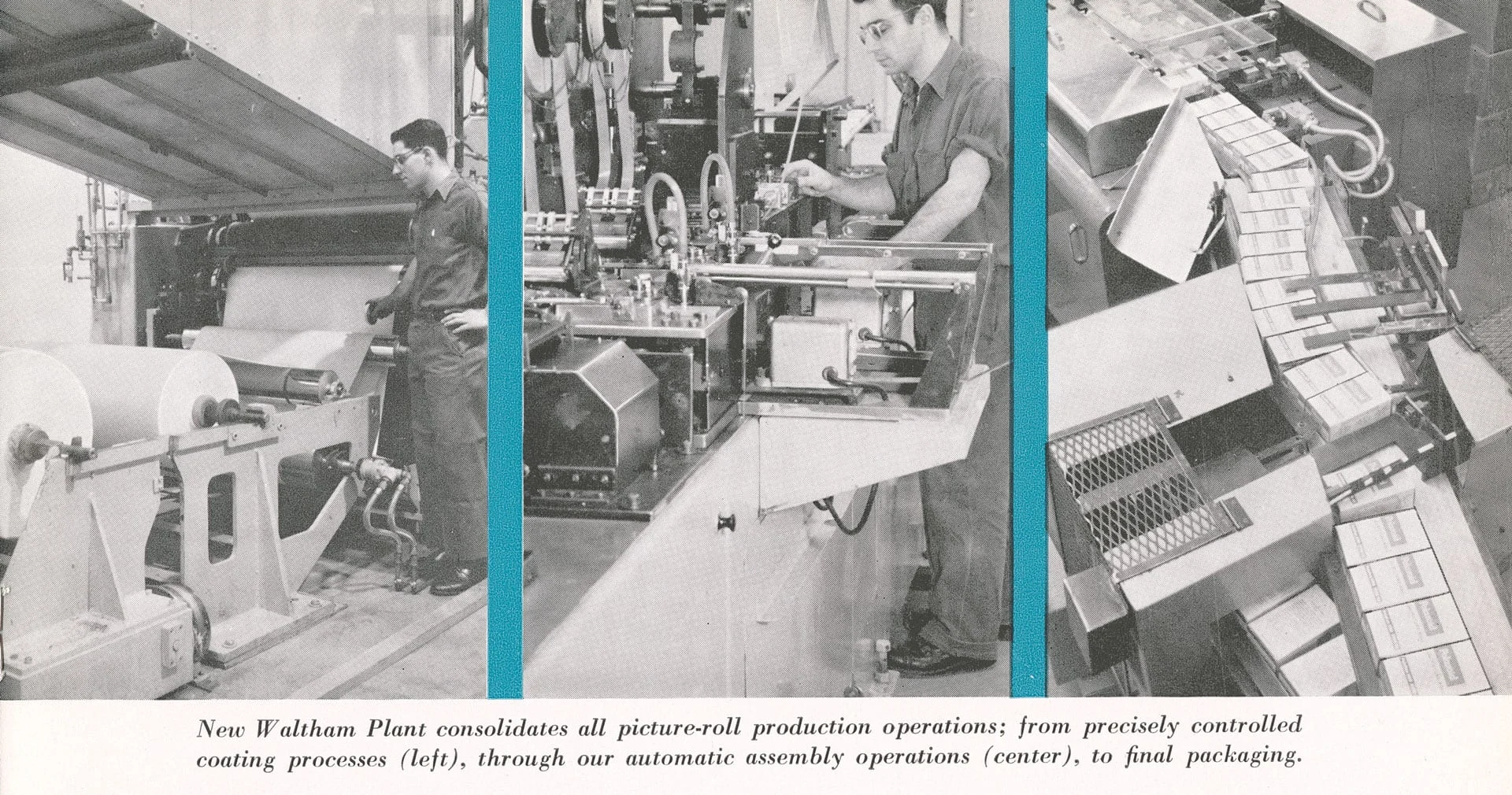

Waltham Plant, Polaroid Corporation Annual Report, 1957. Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, b. I.464, f. 21.

Over the next two and a half decades Morse would participate in Polaroid’s phenomenal growth as its employee numbers, manufacturing plants, and revenues from instant photography increased exponentially. In 1959, Fortune magazine recognized Morse’s contributions as manager of black-and-white film research: “Since 1948 [Land’s] closest associate in developing and improving the sixty-second process has been a Smith arts major named Meroe Morse. . . . Land credits her with many important contributions, especially those leading to Polaroid’s present impressive line of films.”(3) By 1960, photographic products accounted for 97 percent of the company’s total income.(4)

In 1966, Morse became director of special photographic research at Polaroid. A supportive colleague and mentor, she oversaw increasing numbers of employees, whose wellbeing and advancement she nurtured. Inge Reethof remembered that “Everyone who would come to [Morse], with their shoulders hunched, came out 10 feet tall as if their problems were solved. . . . I respected her enormously and she respected all others. . . . She made me feel as if nothing was impossible.”(5)

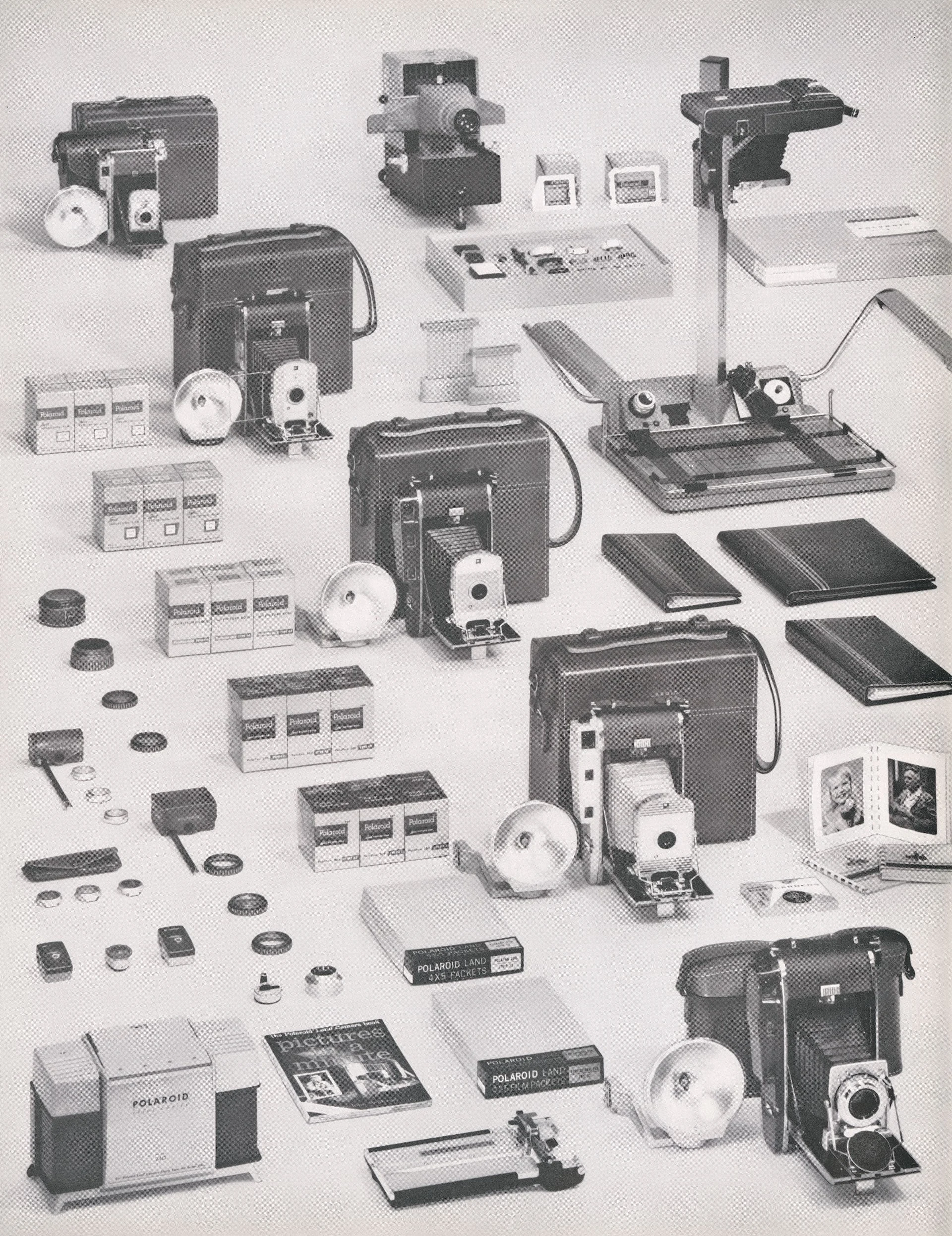

Polaroid camera models and films, Polaroid Corporation Annual Report, 1958. Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, b. I.464, f. 22.

Morse operated shifts around the clock so that the deep thinking and chain of reasoning required for innovation could continue uninterrupted. She knew “which is the right experiment to test an hypothesis, and beyond that the intuitive sense for directing a chain of hypotheses and experiments into a course that leads to a precious new material that has never existed before,” director of color film research Howard Rogers wrote. “Morse appreciated the beauty of elegant concepts and could perceive that there could be new relationships among phenomena, a process we call invention.”(6) Fittingly, Morse’s name appears on numerous sole and joint patents with Land and other Polaroid colleagues.(7)

“Like many people of great effectiveness, [Morse] seemed to have more strength and energy than most people, and could work longer on more problems at once. She somehow could keep her charm and cheerfulness in crises when there was a deadline to meet. The magic produced in her laboratory often seemed to go beyond what could reasonably be expected from the starting materials,” Rogers observed. “I would watch with astonishment and admiration the way the concept of the need would become the concept of the product, and the way the concept of the product would emerge in remarkably short periods into the product itself.”(8)

Letter from Meroë Morse to Edwin Land, February 21, 1951. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, b. VII.3, f. 12.

As both a research and manufacturing enterprise, Polaroid translated ideas into usable technologies, mass produced and marketed its products, and repeated the cycle with the continuous improvement of cameras and films. Morse worked with her colleagues to establish the black-and-white division of the plant in Waltham, Massachusetts, the company’s new manufacturing site that was built to meet the growing demand for Polaroid films. “You, Meroë, are amazing!” Margaretta Kuhlthau wrote to Morse. “I never understood how you juggled the myriad facets of your job. . . . The lab brings you as many problems as are brought to a University Dean!”(9) With energy and focus, Morse coordinated her laboratory’s research efforts with the company’s engineering, production, and marketing divisions to meet overwhelming production demands as the popularity of Polaroid cameras and film exploded.(10)

The magic produced in [Morse’s] laboratory often seemed to go beyond what could reasonably be expected from the starting materials.

Howard Rogers

Polaroid’s marketing department appealed to consumers through eye-catching advertisements and easy-to-read user manuals, and the company distributed cameras and films through dealers and in exhibitions, trade shows, conventions, and theme parks. Polaroid demonstrations took place where cameras were sold and were broadcast on the new medium of television, where personalities like Steve Allen, Gary Allen, and Merv Griffin could demonstrate the one-minute process on the spot. At Polaroid annual meetings, Land dazzled audiences with dramatic rollouts of product prototypes. In 1959 Fortune magazine reported, “The satisfaction of getting results quickly makes Land-camera owners heavy buyers of film. The typical owner of an ordinary camera may buy three or four rolls of film per year. It is not uncommon for owners of the Land camera to buy ten rolls or more. Thus, Polaroid probably sold 15 million to 18 million rolls of film last year, worth $20 million to $25 million to the company.”(11) In addition to its popularity among amateur and professional photographers, instant photography, with its ease of use, cornered the market in the fields of personnel identification, medicine, archaeology, journalism, insurance, construction, and law enforcement.

Morse never served on the board of trustees or as a corporate officer at Polaroid, but as the company grew, her relationship with Land developed into that of trusted advisor and sounding board on a range of business matters—from relationships with outside companies to applications of Polaroid products in the military. From her office, located one floor above Land’s ground-floor office in the Polaroid building on Osborn Street, she sent a steady stream of typed or handwritten letters and reports to Land’s office or wherever he might be on business or vacation. Morse initially addressed Land as “Mr. Land,” after he received an honoary doctorate from Tufts University as “Dr. Land,” and later in their association as “Boss.” Her correspondence included a mix of business and personal notes. “Mr. Skinner told me today to tell you that the Waltham move is wonderfully successful—all the machines are running or ready to run,” she wrote to Land on July 26, 1957, in reference to remarks by David Skinner, vice president of manufacturing, regarding Polaroid’s new plant in Waltham. In the same letter she recounted, “My visit to New York was perfect. . . . We talked art, photography and the history of art incessently, went twice to the Museum of Modern Art—Picasso show and once to the Metropolitan.”(12)

David Skinner, Howard Rogers, Nicholas Dean, Meroë Morse, September 9, 1957. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photograph & Visual Materials Collection, b. X.535, f. 15.

“The impression one gets from Meroë’s copious notes to her boss and many others bespeaks both calm, and wisdom,” Land’s biographer Victor McElheny notes. “People relied on her good sense and eye for the essential.”(13) Photographs reveal Morse’s affable but commanding presence alongside her male colleagues, and many remembered her humor, self-effacing nature, quiet reserve, and steely determination. In essence if not in name, Meroë Morse assumed the role of a chief advisor to the CEO of a major corporation at a time when the responsibilities of C-suite executives were held almost exclusively by men. John and Mary McCann note that Morse’s synergistic abilities made her an “essential photographic scientist in black-and-white films, a superb manager of a very large research group, a major contributor to the company’s success, and a cherished part of Polaroid.”(14)

Polaroid Corporation Annual Report, 1948, 3. Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, Box 1.464, Folder 12.

Eudoxia Muller Woodward, “Notes for Tape for Land Memorial at Hynes Auditorium, Boston, 1991.” Eudoxia Woodward Family Collection

Bello, “The Magic That Made Polaroid,” 155. Original spelling of "Meroe" retained.

Polaroid Corporation Annual Report, 1960, 9. Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, Box 1.464, Folder 24.

Inge Reethof, Interview, 4, 5.

Howard Rogers, “Eulogy to Meroë Morse,” August 15, 1969, 2. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, Box VII.87, Folder 6.

Early in the company’s history, Land understood the importance of patents in enabling Polaroid to properly finance, protect, develop, and market its products.

Rogers, “Eulogy for Meroë Morse,” 2.

Margaretta Kuhlthau to Meroë Morse, April 29, 1959. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, Box VII.2, Folder 3.

David W. Skinner to Edwin H. Land, July 1951. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, Box VII.03. David W. Skinner, vice president of manufacturing, wrote of the problems concerning the backload of orders for black-and-white film that had not been met.

Bello, “The Magic That Made Polaroid,” 126.

Meroë Morse to Edwin H. Land, July 26, 1957, 4. HBS Collection, Box VII.03, Folder 13.

Victor McElheny, personal communication with Melissa Banta, June 21, 2024.

John and Mary McCann, personal communication with Melissa Banta, July 28, 2024.